Factors Affecting the Cost of Hearing Aids

Dr. Rebecca Blaha, lead audiologist at the Pennsylvania Ear Institute (PEI) and assistant professor at the Salus University Osborne College of Audiology (OCA), and Dr. Harvey Abrams, adjunct professor in OCA, discuss the cost of hearing aids in a new podcast.

Blaha: Today's topic, which I think you're uniquely qualified to discuss, is factors affecting the cost of hearing aids. Since you have worked with the Veterans’ Administration (VA) and industry, you have a lot of insight into this area, and I always enjoy your article that you wrote in 2013, “So You Think You Can Build A Hearing Aid For $100. Go Ahead.” I reference this article all the time because I really appreciate how you outlined the factors that influence the cost. This is timely because of the introduction of over-the-counter (OTC) devices as of October of 2022, and I've come across primarily the argument that OTCs are necessary because the prescription devices are too expensive and price a significant portion of people that could benefit out of the purchase.

How can we break this down and discuss — how is it possible that we have prescription devices that cost thousands of dollars and yet OTCs are being less than $100?

Abrams: It's a key question and sort of been driving hearing healthcare policy for the last several years. It began several years ago with a report out of the Presidential Council of Advisors in Science and Technology under the Obama administration that examined reasons for the relatively low uptake of hearing aids in the American adult population, despite the fact that research has demonstrated how hearing aids truly benefit individuals. Not only in terms of their communication abilities, but also their quality of life, and more recent research are very compelling to suggest that hearing aids also help to delay the onset of cognitive dysfunction and specifically dementia. If, in fact, hearing aids are so beneficial, why is it out of the reach of so many Americans, particularly from the economic perspective?

And it wasn't just the economics, it was also what's called the accessibility factor. There's a whole structure involved in getting hearing aids, and this might involve an individual first going to their primary care physician with a complaint of hearing loss. Then the primary care physician referring that individual to an Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT) specialist, that ENT specialist rules out any ear disease. Then the ENT specialist refers to an audiologist, and then the audiologist there does their evaluation and hopefully by that point the individual is still interested in pursuing hearing aids and getting hearing aids. So, you could see how the path and the journey to getting hearing aids is somewhat cumbersome. To add to that, the average cost of a hearing aid is about $2,600. So yes, the question then is, why do hearing aids cost so much money?

And it wasn't just the economics, it was also what's called the accessibility factor. There's a whole structure involved in getting hearing aids, and this might involve an individual first going to their primary care physician with a complaint of hearing loss. Then the primary care physician referring that individual to an Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT) specialist, that ENT specialist rules out any ear disease. Then the ENT specialist refers to an audiologist, and then the audiologist there does their evaluation and hopefully by that point the individual is still interested in pursuing hearing aids and getting hearing aids. So, you could see how the path and the journey to getting hearing aids is somewhat cumbersome. To add to that, the average cost of a hearing aid is about $2,600. So yes, the question then is, why do hearing aids cost so much money?

I think what's been lost in a lot of this discussion is the professional services component. Hearing aids are a medical device, as such the manufacturer, the distribution and the sales must comply with a rigorous set of state and federal regulations, and that has some costs associated as well. That's just the device part of it. While the components may not cost that much, the ability to manufacture millions of these devices in labs and manufacturing facilities that meet state and federal guidelines increases the cost. There are humans who do this. There are engineers involved, there are technicians involved, assembly people involved and their salaries have to be paid. Their fringe benefits have to be paid. Interesting thing about hearing aids and the hearing aid industry is that the technology is rapidly evolving.

I have a laptop here, as many people do, and I'll tell you there hasn't been much change other than perhaps the speed of processing, but there hasn't been much change in personal computers and laptops, the form factor, the design maybe. But in terms of the underlying technology, they operate fairly similarly as they have in the past several years. Hearing aids, on the other hand, seem to undergo technology updates on almost a six-month cycle. And they're pretty impressive types of technology updates.

So, in this little device that we have, bigger maybe my thumb, you have a tremendously powerful computer. You have the ability to identify and separate speech from non-speech. You have multiple microphone systems that are able to reduce sounds coming from behind those sounds that perhaps aren't wanted. You have an ability to stream your peripheral devices, your phone, your music, your TV, into your hearing aid. We've improved the ability to get rid of that high-pitched whistling sound, the feedback that was often the bane of hearing aid users. We continually make them cosmetically better and better. We can take sounds that individual can no longer hear in a very high-pitched range and move those sounds down into the pitch range that the individuals can hear, so they can process that information and on and on and on. This is kind of technology that constantly evolves.

Well, there are engineers that need to design this. There are people like myself in the industry, the researchers that need to test us out on a population of hearing-impaired individuals to make sure that this technology is benefiting the people who are going to use it. And that's not always the case. Sometimes we strike out, we have a really exciting idea, we create a prototype, we test it among hearing impaired people, and low and behold, it just didn't make that much of a difference, or the cost of integrating this into the hearing aid is just not worth the benefits that we're able to achieve.

Well, there are engineers that need to design this. There are people like myself in the industry, the researchers that need to test us out on a population of hearing-impaired individuals to make sure that this technology is benefiting the people who are going to use it. And that's not always the case. Sometimes we strike out, we have a really exciting idea, we create a prototype, we test it among hearing impaired people, and low and behold, it just didn't make that much of a difference, or the cost of integrating this into the hearing aid is just not worth the benefits that we're able to achieve.

It's not unlike the pharmaceutical industry, where you're coming up with drugs to treat diseases. Many times, the drugs don't end up being beneficial or they're not safe, they're not effective. And so, you learn from that and you move on. Same thing happens in the hearing aid industry.

That’s just the device, right? Now with prescription hearing aids, there's a whole other set of costs involved and those are the professional service costs. Up until recently, an individual just couldn't go into Walmart and Costco and pick out a hearing aid on the shelf. You went into an audiology clinic where an audiologist would evaluate your hearing and determine among the many hearing aids that are out there, what is that device best suited for your particular hearing loss and your particular set of communication problems? Don't forget, two people with the same hearing loss may have a whole different set of communication challenges. One of the benefits of going to a clinician is to help identify what the specific communication challenges are so we can select the proper set of device model technology that will best meet your needs.

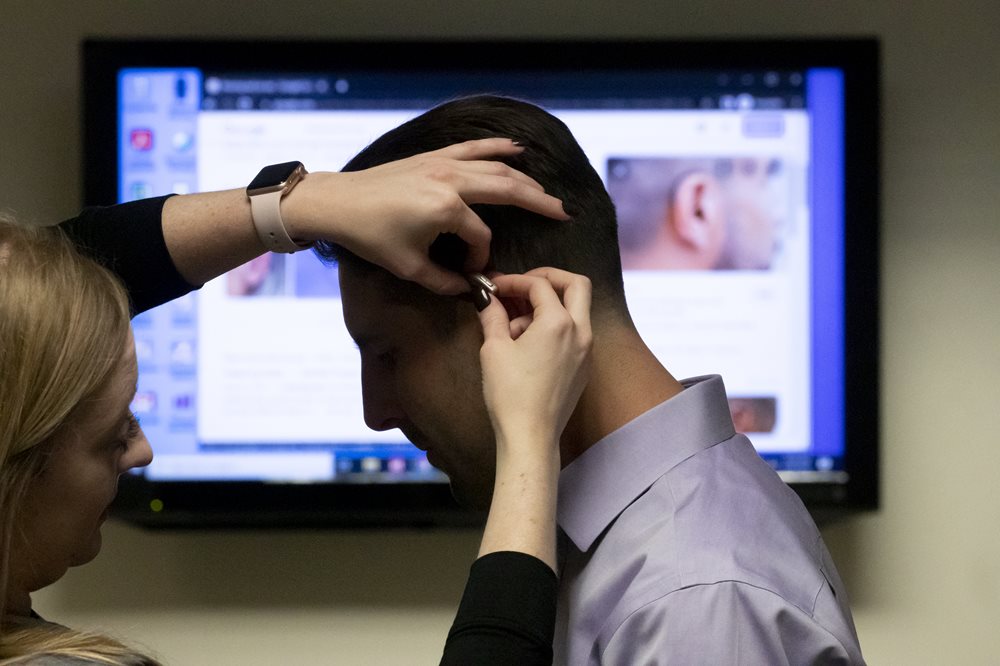

You've got a set of evaluations that you do, a battery of hearing tests. Then in some cases we make an impression of your ear, because everybody's ears are different, and we need to couple and connect the device to the part that goes in the ear and that takes some skill [so] that's a cost associated with the manufacturer of that particular ear mold. Then the hearing aid comes back. As clinicians, we make sure that what's coming out of that hearing aid is what we prescribed. So there's another set of measurements, we call it real ear measures or pro microphone measures, and we modify through software the response of that hearing aid so it meets the particular prescription that we have developed for the individual.

Once that's all done, we spend time instructing the user how to best use and care for the hearing aids, what to expect from the hearing aids, a schedule of use, and then have the individual come back, make any necessary adjustments. Most importantly, measure the extent to which the hearing aids and the treatment that we've provided resolved your communication needs. We may even do more than that. In many cases, the device itself, the hearing aids, the technology, even as wonderful as they are, may not necessarily solve all of the problems of that individual because it could be their hearing loss is so severe that even with the best technology, they still experience challenges in environments such as those where a lot of people are talking in the background. In which case, we may recommend other devices, assistive listening devices or remote microphones, to help reduce the background noise so that the sound coming through the hearing aids only represents the sound from the speaker of interest.

Then there are other rehabilitative tools we might use. We call this auditory training, sort of like brain training except for the ears. A set of games, for instance, that help the individual to better focus on the target of interests and try to ignore the background sounds or games that help them to speed up their processing of sounds. And we might be joined at the hip for years with our patients because over time perhaps their hearing gets worse, we may have to make modifications to the hearing aids, we might add additional therapeutic interventions in time, we might opt for improved technology.

So that's a lot of costs associated with those professional services. As a rule of thumb, of that $2,700 that go into the cost of that hearing aid, only one third of that is the cost of the hardware, the device itself. Two thirds, or $1,800, is all of the professional services that are involved (successfully fitting the device, following the individual and making sure we're getting the optimal results from the devices that we help select and fit).

Blaha: I have seen in many arguments that the comparison to consumer electronics that the price is only related to the product itself and does not have any professional component associated. The arguments are usually, "Okay, well cell phones are extremely complex and have similar components and yet manufactured and sold at lower costs. So if the components are the same, why can't the cost be the same?" And it's really more about the healthcare that goes along with the device itself.

Blaha: I have seen in many arguments that the comparison to consumer electronics that the price is only related to the product itself and does not have any professional component associated. The arguments are usually, "Okay, well cell phones are extremely complex and have similar components and yet manufactured and sold at lower costs. So if the components are the same, why can't the cost be the same?" And it's really more about the healthcare that goes along with the device itself.

The other argument I have heard is that the target audience that is not adopting has mild to moderate hearing loss and they do not perceive any deficit or communication difficulties. How would we address that aspect of the non-adoption?

Abrams: We could probably use eyeglasses as a nice analogy. I, in fact have, these are just ones I got at a drugstore. It's great for reading my journal articles and getting better view of my small print on my iPhone and for computer usage. However, driving I need progressive lenses because I need to see what's out there. Plus, I also need to look at my GPS, which is close by. So, for that, I need to go to an optometrist, I need to get my eyes examined, I need to get more sophisticated lenses. And we can say the same relationship may exist with people with hearing impairment. And that is, if all your needs are essentially getting the TV to a volume that's comfortable for you and other members of the household and perhaps carrying on a conversation one-on-one, and your hearing loss is a mild no worse than a moderate hearing loss, it could be that these over-the-counter devices might suit you reasonably well and that you don't necessarily require a battery of hearing tests. You don't require all of the professional services that go into the selection fitting and follow up of hearing aids.

However, if your hearing is more impaired, it's more likely that these over-the-counter devices, which tend to be less complex, are not likely to meet your needs. The argument for the segmentation, that in fact for people with mild hearing loss, it could be these over-the-counter devices might in fact suit them quite well. However, for people with more complex problems with greater hearing loss, just as I need to go to an optometrist, and many people do for more complex vision problems, you'll need to go to an audiologist to optimize the benefits of hearing aids.

Blaha: I've been recommending a lot of over-the-counter devices for many years. One thing the consumers don't understand is that these are not new products. They were previously classified by the FDA as personal sound amplification products in some instances and can, based on their characteristics, transfer now to the OTC category. Personal sound amplification products are the lower costs amplifier options that initially the FDA stated should not be used for the correction of hearing loss, but yet they accomplished that goal. I recommended them for people who intended to use it more part-time where, like readers, they would only use them for specific listening needs, maybe once or twice a week or maybe once a month for lectures or meetings or social events. So the investment was appropriate for the amount of time they were going to utilize the product.

Blaha: I've been recommending a lot of over-the-counter devices for many years. One thing the consumers don't understand is that these are not new products. They were previously classified by the FDA as personal sound amplification products in some instances and can, based on their characteristics, transfer now to the OTC category. Personal sound amplification products are the lower costs amplifier options that initially the FDA stated should not be used for the correction of hearing loss, but yet they accomplished that goal. I recommended them for people who intended to use it more part-time where, like readers, they would only use them for specific listening needs, maybe once or twice a week or maybe once a month for lectures or meetings or social events. So the investment was appropriate for the amount of time they were going to utilize the product.

We've talked about cost being a big driver and the process of obtaining these, but are there other factors that we might not be considering? Stigma, the use of products being less desirable? What has been your experience with that?

Abrams: In industry, you're very interested to know what are the drivers for hearing aid uptake and what are the reasons people don't purchase hearing aids? What is it about our hearing aids that people like? What is it that they don't like? What is the nature of the journey, the path to getting hearing aids that people like or don't like? And in terms of hearing aid uptake or the lack of uptake over decades, the same reasons seem to emerge. And one is, the most important by the way, not cost. Interestingly, it's that I don't think my hearing loss is bad enough to get hearing aids.

Cost is another, but in fact, I think they're related. It's not that I don't think my hearing loss is bad enough to get hearing aids, but I don't think my hearing loss is bad enough to spend that money for better hearing. It's a value proposition, isn't it? What's value? It's how much we're willing to pay for the benefits that we get. What I would suggest is that the OTCs now have kind of changed the calculation. Now, I might not be willing, I may not think my hearing loss had been enough to pay $2,700 for these devices for better hearing, but maybe I'll be willing to pay $1,000. That's what will be interesting to see over time is whether or not this lowering of the cost, the increased accessibility and affordability, will change that calculation so that people will be willing to pay less money to get better hearing.

Blaha: I know that a lot of audiologists were very worried about the release of OTCs and how that would impact their practice structure, but I see it as probably being a good driver to unbundle services and therefore focus on the value of the professional component so that it is truly, this is what the device aspect costs you, but then this is your healthcare package. I'm hopeful that we can move towards that aspect of practice because it's been debated, should we bundle, which is easier for the practice because you pay a lump sum, or should we unbundle, which I think imparts better education of the patient as to what the process entails. We need to do these because their hearing aids are not wearable out of the box. The product has to be completely customized in order to be beneficial; the consumer's not educated on that aspect.

Any final words that are listeners should be mindful of if they are moving in the direction towards obtaining devices?

Abrams: I would advise everybody that this is new. OTCs have just been approved for sale and purchase by the FDA. Like any new policy, any technology, things are going to change very rapidly. I put out a thousand dollars earlier, but that doesn't necessarily mean that's how much they cost. There's going to be a very wide range of prices for OTCs. There’s going to be a wide range of service delivery models for OTCs. There's going to be a very wide range of technologies in OTCs. Be prepared, keep your eyes open, read up on it, but in the end, be particularly mindful that it's a changing landscape. I'd say the most important thing for consumers to take into account is that they have the ability to try these devices, that they have a return privilege and that there is a warranty. Because if you're buying OTCs, essentially you're pretty much on your own. And so you want to protect yourself, you want to protect your investment. If you don't think these devices are doing what you hope they would do, there's always the prescriptive hearing aid path as well. And in that path, you're more likely to succeed, but it will cost you more.