EMRS and Patient-Centric Care at PEI

During his time in the Navy, Salus University president Dr. Michael H. Mittelman, a two-star admiral, had tweaked something in his foot while running and had to go to the Pentagon clinic to see a podiatrist. She examined Dr. Mittelman and as she was doing so, turned away from him and started typing on her laptop.

During his exam, she had taken her concentration off of her patient and turned her attention to the electronic medical records (EMRs) – also known as electronic health records (EHRs) - on her laptop for what Dr. Mittelman thought was an inordinate amount of time.

He relayed his frustrations to the doctor almost immediately, and after the two had a brief exchange, it got Dr. Mittelman thinking. He started talking to other patients to see if they had experienced the same things he had experienced. And for those who had indeed experienced a situation where the doctor was spending more time with the computer than the patient, the consensus was: (1) They don’t really care about me, all they want to do is get the information in and get the next patient in; (2) They didn’t listen to me because the doctor really didn’t look me in the eye. All they were doing was typing on the computer.

“Most lay patients don’t know what the doctor is doing (on the computer) or that they’re required to do this,” said Dr. Mittelman.

So what began during his Navy career as a concerted effort to practice patient-centric care has carried over into his tenure as Salus president. Prompted by Dr. Mittelman, there is an effort in every clinical facility to make sure student interns take care of the patients first and their EMRs second.

So what began during his Navy career as a concerted effort to practice patient-centric care has carried over into his tenure as Salus president. Prompted by Dr. Mittelman, there is an effort in every clinical facility to make sure student interns take care of the patients first and their EMRs second.

“It’s the de-personalization of care, in my opinion,” he said. “What we’re doing here is not only talking about patient-centric care, but we’re teaching it and we’re forcing the issue. We’re making our students aware of it and we’re reminding them at every step of the way to remember that they’re taking care of the patient. From Day One, we want it to be second nature to our students.”

The introduction of electronic medical records into the doctor’s responsibilities has challenged healthcare providers to find a way to keep the focus on the patients. Since EMRS have been implanted in each of the University’s clinical facilities – The Eye Institute, Pennsylvania Ear Institute and Speech-Language Institute - the collection of data and continuity of care has improved, but care should be taken, according to Dr. Mittelman, not to let the technology infringe on the personal care of the patient.

“Every patient is special, every patient has a story to tell, and as the provider, you need to listen to that story intently and then you act accordingly,” he said. “Our biggest skill should be listening and watching, rather than talking and typing. I feel so strongly about this.”

Audiology – as a profession - comes at patient-centric care a little differently and that’s because it has always taught its students and providers to directly face patients while they’re talking because they are dealing with the hearing-impaired.

“It’s very innate for audiologists,” said Dr. Radhika Aravamudhan, dean of the University’s Osborne College of Audiology. “Our first-year fall term course is called Patient-Centered Clinical Interviewing (it used to be called doctor-patient relationship) and we use actors in that course. Students practice with the actors and the actors give them feedback. Either they sped through the process or they didn’t look at them at all, or make eye contact.”

“It’s very innate for audiologists,” said Dr. Radhika Aravamudhan, dean of the University’s Osborne College of Audiology. “Our first-year fall term course is called Patient-Centered Clinical Interviewing (it used to be called doctor-patient relationship) and we use actors in that course. Students practice with the actors and the actors give them feedback. Either they sped through the process or they didn’t look at them at all, or make eye contact.”

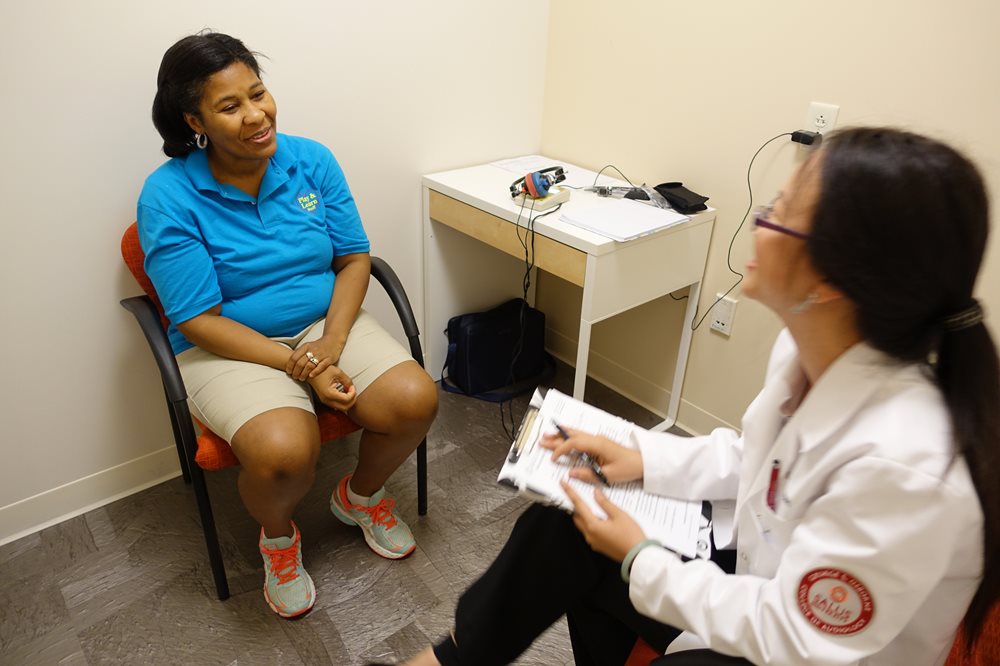

Doctor of Audiology students at Salus and in the program’s main clinical site – the Pennsylvania Ear Institute - are taught to take extra time asking the patients questions before turning toward their computers, inputting the information and then turning back to the patient and continuing the discussion.

“Then before you talk, you have to look at the patient again because they probably have a hearing loss. We’re not going to talk while looking away from the patient because we know they can’t hear us or understand us,” said Dr. Aravamudhan.

While the EMR is a tool to keep records, it does not take the place of building a relationship with the patient.

“If you’re not looking at them in the eye, if you’re not in a discussion and not really listening to their problems, you’re not building that rapport,” she said. “You might be able to give them a diagnosis, but they’re not coming back to you for rehab because they didn’t build that relationship. They didn’t think they could trust you on the next step.”

Dr. Mittelman believes EMRs are a useful tool and doesn’t discount the technological advances provided by electronic medical records. But they shouldn’t become a stumbling block for developing the provider-patient relationship.

“I think they’re wonderful, except they can be a curse. They take more time to see a patient, they take your attention off the patient and they de-personalize the patient,” he said. “It’s all about effective communication, building trust and ensuring that the patient understands that they really are at the center of this diagram, they’re not peripheral to that computer.”